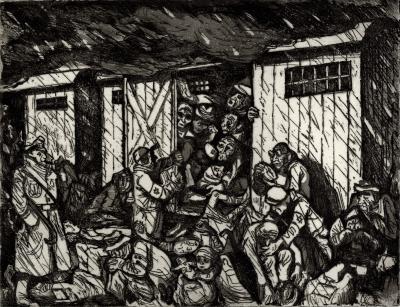

Transport!

The most feared word in Theresienstadt was transport. ‘To be put on a transport’ meant to be deported eastwards – usually to Auschwitz – to conditions that were far worse than those in Theresienstadt. Although the prisoners in Theresienstadt did not know precisely what was going on in the eastern camps, they did have a premonition. Rumours about gas chambers and inhuman treatment had also reached Theresienstadt.

The transports

“Transport! In Theresienstadt, no word was so terrible and frightening as that. The prisoners trembled even at the thought of it. Not only because of the closed and ominous freight cars or the fact that people were stuffed into them without food or drink for many days, but also because of what was awaiting them at their new destination. Usually, the transports were to Birkenau in Poland, where despite of its isolation from the outside world, it was known that besides harder work, less and worse food and beatings by the SS, there were also gas chambers.”

Transports from Theresienstadt

The first transport left Theresienstadt for Riga on 9 January 1942. The first transport from Theresien-stadt to Auschwitz left on 26 October 1942. Out of the 140.000 people who were imprisoned in Theresienstadt during the camp's existence 88.000 were put on a transport. The majority of the deportées were sent to the extermi-nation camps of Auschwitz and Treblinka or to Maly Trostinets near Minsk in what is now Belarus. Most of these people were killed in gas chambers or in other facillities of mass extermination.

The agreement

Both the Danish Jews and the stateless deportees from Denmark were protected against further deportation by an agreement made between Adolf Eichmann, Head of the Office for Jewish Affairs in Berlin and Werner Best, the highest ranking Nazi in Denmark. However, the prisoners knew nothing of this agreement. Like everyone else in Theresienstadt, they feared for their lives every time people were selected for a transport.

Paul Aron lived for a while with 42 boys in one of Theresienstadt’s orphanages. Here, he was the only Danish boy. One day he learned that all the boys – except him – were being put on a transport. After the war, he wrote a poem about that day:

“October 26, 1944

I look around at the empty beds

Where 42 living boys had lain until the order came:

The expected transport

Now they should leave

The were called up by name, one after another

Forty-two pairs of thin freezing legs

Stood up in a row, each with his backpack

Now they are gone

Boys that played and laughed and fought

And cried when thoughts of home were lit

They wanted to live, were full of longing

In the ghetto’s prison

In the poor naked sacks of straw

Where the boys still lay that morning

Forty-two living boys happy for life

Empty beds”

Transport helpers

The prisoners who were not put in transport were forced to carry out various tasks when the transports were scheduled to leave Theresienstadt. Paul Aron, for example, was ordered to play on the day when the boys from his room were transported. Other Danish prisoners were ordered to work as transport helpers.

“There came messages in the evening: Prisoner number such and such is going to be on a transport, and number such will be in a transport, and people were extremely agitated. I was very close to that whole act many times. I was supposed to remove prosthetic devices. Have you ever taken an eye out of a living person? A glass eye? Teeth, which were carefully sorted? Artificial arms should be placed on the right. Legs on the left. These spare parts were meant to be reused by Germany’s surviving soldiers.

I had to remove the prostheses from these poor people. From 1914 to 1918, they had been soldiers in the German army and fought for the great fatherland; they had risked their lives and limbs. Now, they received Germany’s thanks in this way. Everything was taken from them. […]

The cattle wagons’ doors were locked and bolted – and we stood there at night and could do nothing. We couldn’t cry – we felt paralyzed. And often the wagons stayed there, not one, but two or three days before they were sent off.”