In Theresienstadt

The prisoners from Denmark arrived at a place that in many ways resembled a regular town, but was not. Although there was supposedly Jewish self-rule in Theresienstadt, everything was done within the framework stipulated by the SS. The town’s residents were Jewish prisoners; they were starving and they were forced to work hard.

From Denmark to Theresienstadt

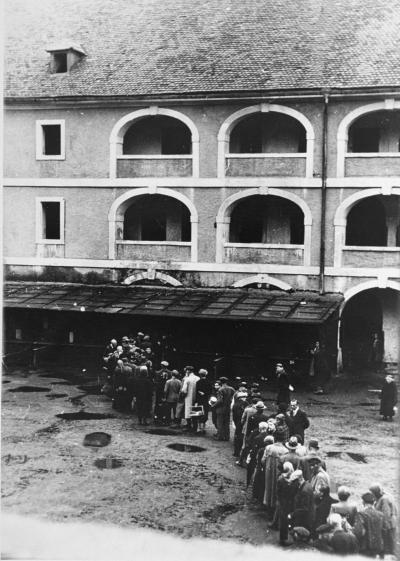

Theresienstadt was one of the many camps and ghettos established by Nazi Germany as part of the persecution of European Jews. There were about 6500 Jews in Denmark in 1943, and in October that year, most of them succeeded in fleeing to Sweden. However, 472 people were deported during the following months, either because they were Jews, or because they were considered to be Jews by the Nazis. Almost all of them were deported to Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia – now the Czech Republic.

The history of Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt is located 50 km. north of Prague on the way to Dresden. The town was founded around 1780. At that time, Theresienstadt was part of Austria-Hungary and was actually a fortress. As long ago as 1864, Danish prisoners were incarcerated in Theresienstadt. They were Danish soldiers who were taken as prisoners of war during the battle of Dybbøl on 18 April 1864. Theresienstadt’s status as fortress ended in 1888, but the town’s many barracks continued to be used. The German army occupied Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939; and in November 1941, the first Jews from Prague were sent to Theresienstadt.

An “as-if” town

In 1944, the Austrian prisoner Leo Strauss wrote the poem,“Als ob” – “As-if”. The poem describes Theresienstadt as resembling an ordinary town without being one. The first verse goes:

”Ich kenn ein kleines Städtchen,

Ein Städtchen ganz tiptop –

Ich nenn es nicht beim Namen,

Ich nenn’s die stadt Als-ob.”

In the poem, he describes the ‘as-if town’, where people live their lives as if they were lives, and listen to rumours as if they were the truth. They drink “as-if coffee” and eat “as-if food”. They lie on the floor as if it were a bed. And they accept their harsh fate as if it were not so harsh and speak about the future as if it were already there.

‘Self-rule’

Theresienstadt had so-called Jewish self-administration. This meant that an Elder of the Jews (Judenälteste) was appointed to lead the so-called Council of Jewish Elders (Judenrat), which might be compared to a mayor and a city council. But in reality, they had no power to speak of. Everything had to be approved by the camp commander. It was he who issued the orders in the first place, and then the Council of Jewish Elders could decide how the order should be implemented. For example, the council would receive an order to deport a certain number of prisoners to Auschwitz. The council was then left to make the hard decision of naming which prisoners to deport. To the extent it was possible, the council attempted to improve conditions in the camp. They were responsible for the camp’s health services, delegating work in the camp, and the camp’s cultural activities.

The prisoners in Theresienstadt

The first group of imprisoned Jews arrived in Theresien-stadt from Prague on 24 November 1941. In the beginning, Chech Jews were being sent to Theresienstadt but shortly after also Austrian and German Jews arrived. From Czechoslovakia came children, women, youngsters and elderly people. The German and Austrian Jews were mostly old people and war veterans who had recieved medals for their contributions in World War 1. There were also artists and scientists; people of cultural standing whom the Nazis did not want to kill straight away. Later also Danish and Dutch Jews arrived.

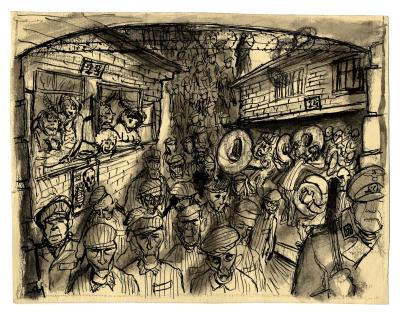

Arrival

When the prisoners arrived at Theresienstadt, their entire luggage was searched and everything of value was confiscated. The prisoners were given yellow stars of cloth inscribed with ’Jude’ along with a so-called transport number. The number was not tattooed on their skin as it was in Auschwitz, but they had to remember their number – the number was the prisoner’s identity.

”When we returned to our luggage and sat on the ground, my mother explained that the transport number I had received had to be memorized. To anyone who asked, I should be able to state the number immediately. My mother then said in a sharp tone, so that I understood it was serious, that even if she woke me in the middle of the night, I should be able to remember my number and say it immediately. Otherwise, the Germans would shoot me. My number was XXV/3-129, but I had not yet learned Roman numbers, so I had to learn to say it with Latin letters. I had to say: XXV slash three slash one hundred and twenty-nine. My mother repeated it to me over and over again, until she was sure that I had memorized it. The numbers meant: transport 25, third group, and then my personal number: 129.”

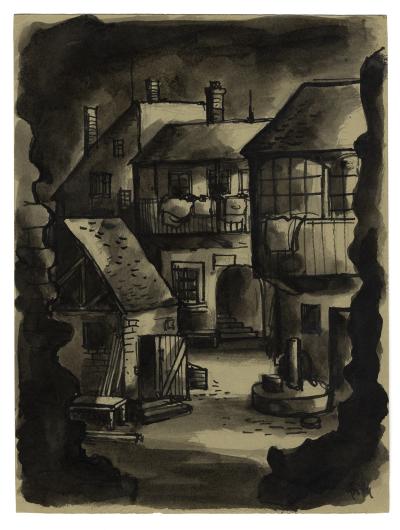

Housing

There were different categories of prisoners in Theresienstadt, and some prisoners had better housing conditions than others.

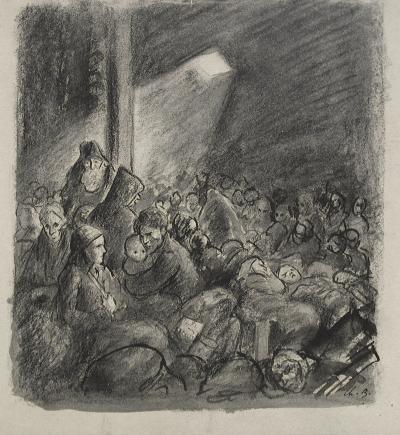

Most families were separated and lived in crowded attics in the old military barracks – in large rooms with bunk beds, some for women, often together with the smaller children, and others for men. Many children lived in a children’s home in Theresienstadt. Among the Danish prisoners, a little group of ’prominent’ prisoners had certain privileges: the families were allowed to live in a room together. Sometimes, several such ’prominent’ families were put in one room together, but the families were not separated. Upon arrival, those women who could work were housed in the Hamburg barracks, and the men in the attic of the Hannover barracks. One survivor called this attic Hotel Floh – Hotel of Fleas.

For the people who were too old and weak to work, conditions were even worse:

”Some of the elderly were assigned to the Cavalier barracks. In order to understand the conditions there, you must know that the deep, narrow rooms had only one window at one end and were otherwise dark all dag long – to save electricity, only one little bulb from the high ceiling was lit, but only when it was completely dark – and the rooms had previously been used for storing potatoes. The walls were damaged and the old people kept stumbling because the stone floor was torn up in places. Dust and dirt were everywhere. It was impossible to keep the place even slightly clean with 40-50-70, yes, even 100 people, living in this dark room.”

Work

The prisoners who were able to work were sent to do hard physical labour – both adults and children. The prisoners worked in the various workshops in Theresienstadt or in the SS officers’ gardens or they built roads. In one such workshop the workers split mica, a mineral used in the war industry. Splitting mica into thin flakes was both difficult and tedious. Other workshops produced uniforms, baked bread or made shoes. Some products were sent to Germany; others were used in the camp – bread, for example. The prisoners could also be put to work in the camp’s hospital, post office or nursing home. Some of the young men worked as pallbearers.

Family time

After a long, hard workday, the families did not have much time to be together, and the crowded conditions in the big rooms where they slept did not make it easier. It was impossible to maintain a normal family life, but they tried anyway. One Danish prisoner later described an evening in Theresienstadt:

“We sat on the edge of our daughter’s bed and ate our dinner, when the neighbour who slept in the top bunk came, a tall stout German woman. She climbed the ladder up to her bed and sat with her legs hanging down just over our heads. She had on long rubber boots, and they were covered with gooey brown mud!

‘Would you please take your boots away,’ I asked her in a friendly way, ‘we are eating.’

‘No, I will not!’ she answered.

‘Your boots are filthy and we can’t eat,’ I continued.

‘You’re not even allowed to be here!’ she said.

‘Take those boots away!’ I became angry: ‘Take the boots away!’ and I gave them a push/shoved them.

Then, there was a scream; she called the room officer: ‘Madame Cohen – a man!!!’

I had to give up.

The following days we sat on the other side of the bunk, on my wife’s bed and ate our dinner. Over at our daughter’s bed there was light. A bulb hung from the ceiling, but here it was dark; it was sad and miserable. We had been forced out of paradise – the tiny bit of enjoyment to be found in this hell. The tiny bit of light we enjoyed with our dinner had been stolen from us.”

Hunger

The prisoners in Theresienstadt were starved. The food they received in the camp was terrible. Every third day they received a ration of bread to eat with a thin, greyish soup. There was never any fruit, vegetables or eggs and only very rarely milk for the children. In all, their daily meals provided about 1000 calories, while an adult needs about 3000 calories daily. Therefore, many people in the camp died of hunger or malnutrition. The youngsters who worked extra hard received a slightly larger food ration than the other prisoners. The elderly often sat beside the food queue and begged for food. Alex Eisenberg described it in this way:

“Finally, it is my turn. A ladleful is dumped into my bowl without a handle. The prisoners behind me are already shoving me aside while I greedily take the first gulp of the grey, thin tasteless soup. Illusion is totally destroyed. If only I had kept a little bread. You’re supposed to have bread, when you eat soup! But I keep hoping that there is at least a bit of grain at the bottom. I take couple of cautious steps out into the courtyard so as not to spill any of the liquid that still contains a precious hope.

I walk by some elderly people. From their outstretched hands and wrists, I can see how spider-web thin, yes, how hungry until death they are. They hold out their bowls, so heavy in their hands. They say: “Junger Herr! Nehmen Sie die Suppe?”

This ‘young man’ is about to sink into the cold mud in shame. I know exactly how hungry they are, that they are dying from starvation. I am a pallbearer. We drive around every day and pick up the dead. Mostly old people. So transparent. So light. Almost no clothes. I carry them down the cold stone steps. Lay them on the platform of the four-wheeled wagon, which we then push and pull to the next corpse to be laid on top. When the wagon is full, we push it to the crematorium.

Relentlessly!

“Young man! Don’t you want your soup?”

Food parcels

During the spring of 1944, conditions changed drastically for the group of Danish prisoners. They began to receive food parcels sent from Denmark. At first, ordinary people, e.g. organized by a network of priests, simply sent parcels through the postal service from Denmark to Theresienstadt. They had not asked permission – they just did it, and the parcels actually arrived at the camp. In summer 1944, official permission was given for the Danes to receive parcels from home, and the Red Cross took over some of the deliveries. The parcels were mostly paid for by the Social Ministry, which transferred funds to “Fund of 1944 for Social and Humanitarian Purposes”. The neutral name referred to the parcels bound for Theresienstadt, and in this way, the government could give money without the occupation force knowing about it.

Prisoners from other countries could also receive food parcels, but due to famine in most of the occupied countries, it was difficult to obtain permission to send food out of the country. Therefore, the only prisoners who received food parcels were those who were lucky enough to know someone who would and could receive permission to send them.

Food!

In the camp, the prisoners had to pick up their parcels at the post office. They also had to pay a kind of customs in order to receive them. They paid the customs from the ‘wages’ they received for working in the camp. In Theresienstadt, special money was used, but for the most part, nothing could be bought with it. There was a shop, where they could buy mustard powder and used toothbrushes, but not real food.

With the arrival of the food parcels, the prisoners from Denmark got a substantial supplement to the poor camp food. They were suddenly ‘rich’ and could trade food for other things they lacked, like shoes, clothing or an extra blanket. The Danish prisoners were of course very happy and grateful for the food, even though it was not always fresh after the long train trip through war-torn Europe.

“Ah, no – the cheese in the parcels would often move. It had often been there for weeks, months, and was full of mites, but that didn’t keep anyone from eating it. Once, someone sent us eggs. We received a week-old egg mass that had ruined everything else. We both cried and raged.

There were specific rules for how often we were allowed to receive parcels – about once a month. And many times it was just half a parcel. Just that bit of fat in a sausage was of immeasurable importance, if we should hope to survive.”